After the May 3rd Incident Became Obsessed With Depicting Human Suffering in His Art

T he lilac was in full bloom when a group of boys from the Strand school in Brixton and Kenneth Keast, their 27-year-one-time principal, left Freiburg for the opening hike of their x-day Easter trekking tour in the southern Black Forest. It was the morning of 17 Apr 1936, equally they prepare off for the village of Todtnauberg, over xv miles abroad, across the summit of the Schauinsland mount. By the fourth dimension they emerged from a wood about three hours later, snow was falling steadily only they were full of spring-time optimism. The boys bankrupt ranks to throw snowballs.

Keast noted that some of his boys – who wore shorts, mackintoshes, and even sandals, rather than appropriate gear for hiking through snowy mountains – were kickoff to find the going tough. With the snowfall worsening, he put a end to their skylarking and urged them to concentrate on the path ahead.

When they had prepare out from their youth hostel that morning, Keast had been warned that the snow would make his planned route chancy. Fifty-fifty without snow, the locals considered it a challenge. The weather map for 17 April that hung in the hostel gave clear indication that conditions were going to turn. The previous day, the tourist function had warned Keast about the budgeted storm, to which his response was: "The English are used to sudden changes in the weather condition." The 13-twelvemonth-former Ken Osborne, who had already written his offset postcard home, wrote in his small black notebook: "Had breakfast. Left Freiburg about nine o'clock. It was snowing and we lost our fashion."

With snow at present falling heavily, and having lost the path and circled back on themselves, they were soon behind schedule. Keast stopped at an inn to ask for directions. The landlady brash him that the paths and signposts would be buried in snow, at which the schoolmaster shrugged and said they would "brush it off".

By at present they were forced to kick their way through the snow. On an open up hillside, they met two woodcutters heading dwelling house considering they could not continue their work. They advised Keast to take a path to the left of the valley. At around 3.15pm, they passed the local postman, Otto Steiert, who urgently warned Keast against continuing the ascent. Steiert offered to aid the party return to Freiburg, or to bring them to the shelter of the miners' hostel, where they would have institute beds and nutrient. Keast declined.

He had not yet started to panic, but the glace, slow-going conditions prompted the teacher to stop and question each male child equally to how he felt. Some complained of cold. But Keast decided that to go dorsum would be more than perilous than standing towards the nearby hamlet of Hofsgrund, where he hoped to find shelter in a hotel or peasant's house. Unfortunately, the map Keast had received from the School Travel Service in London, which had organised the trip, had a calibration of 1:100,000, meaning major routes were shown, only not the gradients or the small pathways. This meant he failed to realise that between them and the village rose the steepest and most dramatic ridge of the Schauinsland. Every bit a result the boys, now weary, cold and moisture, took a gruelling route upward the Kappler Wand, a 600-metre, seventy% gradient face.

The start male child to collapse was Jack Alexander Eaton, the school's fourteen-year-sometime battle champion. He was given an orange and a slice of cake and told to "buck up".

When they left the protection of the rock and came out on to the ridge, the decrepit grouping was exposed to the force of the wind. Had they moved eastwards into the wind, they would accept arrived at the safety of the meridian station inside less than a mile. Instead they were pushed westwards and they chop-chop became disoriented. By at present Eaton and two of the youngest boys had to be carried. Three more boys were in great difficulty.

Hofsgrund was a typical Black Wood village of simply 300 inhabitants, consisting of ane inn, a church and a scattering of farmhouses with steeply pitched slate roofs, where animals and humans shared living quarters over the long winters. On that bleak April evening, the 7pm chimes of Hofsgrund'southward church bells were carried on the wind. Keast sent ii of the older boys to follow the management of the bells down the colina, leaving most of the others on the slopes trying desperately to revive those who had collapsed.

It took about an hour for the 2 boys to achieve a farmstead on the outskirts of Hofsgrund. Like most villagers, Eugen Schweizer had spent the mean solar day at habitation, and was bracing himself to get out to run across the weekly bread commitment when two boys, bareheaded and dressed in brusk trousers, knocked on the door, and spluttered in cleaved High german: "Zwei Isle of mann, krank am Berg" (2 men sick on the mountain).

Schweizer summoned a party of rescuers, hammering on the window of the Gasthaus zum Hof, the village inn where he had seen that lanterns were called-for and people were playing cards. They put on skis and headed out towards the road. By at present the trekking group was strewn beyond a broad stretch of terrain. Some of those who had collapsed were almost completely covered in snow. Some of the boys were making their way downwardly the colina, and Schweizer stumbled across two lying motionless in the snow. Hermann Lorenz, the grocer, brought one unconscious boy into his store, while a farmer, Reinhold Gutmann, carried the other on his back to a nearby farmhouse. The men had planned to use their skis like stretchers and lie the exhausted boys on them, but the snow proved too deep and powdery. Instead they fetched a sledge on which to drag them downward. Stanley Lyons, who had collapsed about 10 yards from the inn, was probably already dead, only the rescuers tried to revive him.

Schweizer, forth with four other local farmers, headed further upwards the mount, carrying one carbide lamp betwixt them. They found the schoolmaster Keast next to two other unconscious boys. In German, Keast told them the size of the group. Later climbing lonely upwards the mountain for a full 45 minutes, Hubert Wissler, 1 of the commencement to take heeded the cries for help, constitute iii boys suffering from exposure. The rescue attempt lasted until well after 11pm. The rescuers' apparel were soaked from the snow, their bodies drenched in sweat.

A doctor holidaying nearby was summoned to attend to the virtually serious cases. The rest of the boys were beaten with brooms to shake off the snow and become their apportionment going, before beingness allowed anywhere nearly the huge woodburning stove. They were wrapped in blankets and given food and coffee before beingness put to bed. In spite of these efforts, by the end of the evening, four of the boys were dead: Francis Bourdillon, 12, Peter Ellercamp, xiii, Lyons, fourteen, and Eaton, who was two months away from his 15th birthday. Arthur Roberts and Roy Witham, both 14, were still dangerously ill.

Roberts and Witham were taken to the academy hospital in Freiburg the next twenty-four hours, only Witham died without regaining consciousness. The bodies of the expressionless boys were placed in the cellar of the Hofsgrund village hall, and later transported to Freiburg and laid in the chapel of residue at the principal cemetery. The survivors were taken by sledge to a nearby village, where the route was clear plenty for them to travel by bus to Freiburg, where they had medical checks. So dazed were the survivors, none of them had taken in the gravity of what had happened. They didn't understand until two days later that five of their school friends were dead, and one was fighting for his life. Nor could they accept known that they would become embroiled in a Nazi propaganda coup of spectacular proportions.

M ost Britons learned of the deaths on Schauinsland from the lunchtime editions of the next mean solar day'due south papers. The printing called it the "Black Wood tragedy", and over the post-obit days the papers were full of accounts of "boys' blizzard battle", and how they had been "saved by the church bells", the "master's efforts to save his boys", and the Hofsgrunder skiers' "rescue dash".

The boys were instructed to write to their parents and reassure them. Ken Osborne sent a postcard habitation to Tooting, depicting a snow-covered mural, on which he wrote: "Honey Mum … as nosotros got lost, information technology might be in the papers and then we have been told to write and say I am quite safe."

Relations between Britain and Germany had become increasingly tense in the three years since Hitler's rise to power. Just days before, Britain had held a formalism funeral procession for Leopold von Hoesch, the German ambassador to Britain, who had been viewed equally ane of the best hopes of maintaining peaceful Anglo-German relations. His bury, draped in a swastika, was taken down the Mall accompanied by British guardsmen and onlookers giving the Nazi salute. A piper played a lament every bit information technology was loaded on to a warship at Dover.

It was quickly perceived in Germany that political capital could be fabricated from the Black Forest tragedy. Baldur von Schirach, the leader of the Hitler Youth move, telegraphed Britain's ambassador to Germany, informing him that a wreath from the "German Youth" would be placed on each of the boys' coffins to signal their "heartfelt and deep sympathy", and that a spotter of Hitler Youth from the region would stand baby-sit over them until transport to their homeland could be arranged.

Newspapers in Germany and Britain carried photographs on their front end pages of uniformed Freiburg Hitler Youth members keeping a vigil over the coffins at the city'southward main cemetery, against a properties of swastikas aslope union jacks. Thousands of Freiburgers came to pay their respects, in the presence of Keast, seven of the older boys, and British diplomats. Friedhelm Kemper, the local Hitler Youth leader, gave a voice communication in which he talked of the "will of understanding and peace" between the German and English "comrades". 15 of the younger boys had, meanwhile, been left in the care of older Hitler Youth members who entertained them with a game of football game and took them for a ride on an double-decker.

The Monday was Hitler's birthday, offering some other opportunity for a procession. Local dignitaries paraded to the main railway station. A baby-sit of honor, hundreds-strong, was formed past the various units of the Hitler Youth, its female equivalent, the Spousal relationship of High german Girls, as well as hundreds of Freiburg schoolchildren, who lined the road and watched as the coffins were loaded on to a train. The surviving boys who clambered on board two separate trains were accompanied by 20 members of the Hitler Youth as it made its way through Germany and up to the border at Aachen.

By now the Hitler Youth were being credited with helping in the rescue. Die Volksjugend, the Baden branch of the Hitler Youth's ain newspaper, praised its members for their participation. A printing release issued by the Reich's Youth Press Service stated the dead had "fallen in battle so equally to further the open, honest friendship betwixt nations". The Lord Mayor of Freiburg, Franz Kerber, went and then far equally to write to the father of one of the deceased that the boys had been "sacrificed" so as to become "standard bearers for the of import aspects of understanding between our two neat nations".

Although not a Nazi stronghold, Freiburg had its own reasons for playing along with Berlin's propaganda offensive. Local officials were painfully aware that the disaster could harm the tourism industry in the Blackness Woods region, which was extremely popular with British tourists and, in particular, school parties.

The campaign certainly caught the attention of many ordinary Germans, thousands of whom lined the 330-mile stretch via Frankfurt to the Belgian border to pay their respects. Many threw sweets to the English language boys, who leaned out of the train windows to marvel at the spectacle. Several of their parents wrote personal letters to Hitler, thanking him for the thousand send-off, and for the German land railways' waiving of the £lx fee each family should take been charged for the conveyance of their sons' coffins.

T he families anxiously waiting in London were informed by telegram on 21 April that their boys would arrive at Victoria station at 4.20 that afternoon. "Great crowds to see united states go far," Ken Osborne wrote on the final folio of his Diary of a German language Trip, noting that he had been interviewed by a reporter from the tabloid newspaper, the Daily Sketch, on the railroad train.

The mean solar day after the survivors' render, a special railway van that had been adjusted to resemble a small chapel and attached to the postal service railroad train from Harwich, arrived in London at 8.21am. Information technology contained the bodies of the expressionless boys, in coffins of Black Forest timber – "from the very woods in which they perished", as one reporter put it. They were met by relatives and schoolmates as well every bit officials from the teaching department, all of whom removed their hats and stood silent on the platform of Liverpool Street station. So many people gathered on the upper walkways overlooking the platform that extra police had to exist called in to control the crowds.

When the van door was opened, the boys' parents stepped inside to see the coffins of their sons draped with spousal relationship jacks, each bearing a white slip of paper on which their proper noun was written. The platform was carpeted with floral tributes, including huge evergreen and pine cone wreaths from the Black Forest, tied with scarlet and white ribbons and bearing the swastika, with the inscription: "To our English language comrades". There were wreaths from Adolf Hitler and the British ambassador.

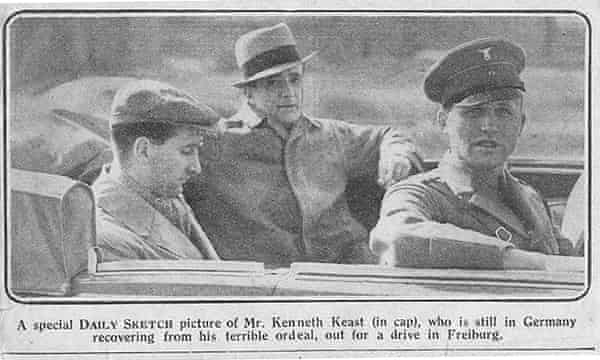

Keast remained in Germany for several more days as a guest of the Hitler Youth. The Daily Sketch ran a photograph of him in an open-top machine, dressed in a fabric cap and scarf, "out for a bulldoze in Freiburg" with the local leader of the Hitler Youth and a representative of the Gestapo, the Nazi state law. He addressed his thanks to the Hofsgrunder in a alphabetic character, published in a German newspaper, stating: "We can never forget the superhuman efforts of the people of Hofsgrund who did everything to bring us to rubber … All this has brought nearer to usa the country which previously had been estranged."

In one case he finally returned to London, Keast escaped the scrum of reporters outside his parents' house, by heading to Bournemouth, where he met a boyfriend teacher, Mary Beaumont Medd, with whom he was evidently in love. In a letter to her on 24 April from the Solent Cliffs hotel, he complained of existence unable to sleep but thanked her for restoring him "to any sanity I can promise to approach".

In a bizarre admission for a homo to make less than a week afterward the deaths of the boys in his care, he added: "And after I lay down last night I could not help saying … that in spite of everything, I had had the happiest solar day of my life."

One by one over the following days, the dead boys were buried in various London cemeteries, in Streatham, Woking and Due east Ham. Jack Alexander Eaton'south funeral on the afternoon of Friday 1 May, in Streatham, was attended by a thousand mourners. The hearse was drawn by six horses, with boys from the school, including some of the survivors, forming a guard of honor. Floral tributes from the Hitler Youth and Adolf Hitler were on prominent display.

J ack Eaton described his 14-year-old son as existence "all that I myself wanted to exist". Eaton had built up a successful construction business in south London, and was proud of his status as a self-fabricated human being. The day afterwards the disaster, he was already making his mode to Freiburg to piece together what had led to the death of his only son.

Eaton flew to Cologne and took the train to Freiburg to trace the route the boys had taken, accompanied by a solicitor and an interpreter. He interviewed the rescuers, and spoke to other witnesses who told him they had repeatedly warned the party to plough back. He found the 1:100,000 map Keast had used – which was by at present in the keeping of Freiburg's public prosecutor.

Eaton vowed he would not rest until the regime launched a public research into the disaster. In a 10-folio report of his ain investigation entitled Black Forest Tragedy – The Truth, which he distributed to newspapers, politicians and every family involved, he wrote: "I am determined to fight on to the bitter end" on behalf of his boy who "was everything to me" as well every bit for the other "little heroes who should take been with us today and for many years to come." The report was illustrated with a photograph of Jack in his cricket whites and poised with a bat, a quiff framing his grinning confront.

Eaton's detailed reconstruction of the school trip noted that, had it not been for the church building bells of Hofsgrund, "they would probably all have perished". He concluded that Keast – a popular teacher of High german and sport, who had been head boy at the Strand school before going on to Cambridge – was "certainly not fit to take 27 boys from the school to Clapham Mutual, let alone on such a journey to a foreign land". He claimed it was Keast'south "open dislike" of Germans that had probably led him to feel it would have been "degrading for him to accept a German'southward give-and-take of advice".

The idea of erecting a memorial to the events of 17 April were showtime raised publicly effectually a month subsequently in the official Nazi newspaper the Alemannen, every bit well every bit in the British printing. The people of Hofsgrund had mooted the idea early on, communicating to Freiburg's tourism manager their want for an inscription carved into the rock, which would accept recalled the incident and best-selling that without the locals' assistance, many more would have died. Afterwards much vacillating, the Hitler Youth took over management of the project.

Von Schirach, head of the local Hitler Youth, was fully backside the idea. But he had far grander plans, and commissioned a renowned professor of fine art, Hermann Alker, to come up up with an ambitious design. Schirach stressed it was something in which the Führer himself was taking a personal involvement.

The Engländerdenkmal – a towering gateway made up of two huge upright stones of Black Forest granite inscribed with the names of the boys, and a third rock linking them on top and decked with the Nazi eagle and a swastika, was finally completed in the summer of 1938. It stood on the mountainside, 800m above the village of Hofsgrund.

The memorial was due to exist inaugurated on 12 Oct, in the presence of a member of the British purple family, the head of the Lookout man motility, Sir Robert Baden-Powell, and the British ambassador, in a ceremony which once again was supposed to assert the German-British friendship. The inscription concluded: "The youth of Adolf Hitler honours the memory of these English language sporting comrades with this memorial."

All the same any political interest there had been in the memorial promptly evaporated in the wake ofthe Munich Agreement of September 1938, which controversially gave Hitler control of the Sudetenland. Subsequently Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, there were repeated initiatives to tear it down. While that did not happen, information technology was never inaugurated.

Past the offset ceremony of his son's death, Jack Eaton had commissioned a Freiburg sculptor to make a separate memorial to his son, which in itself expressed the divide that by now existed between him and the other bereaved parents and the schoolhouse, over who was to blame.

That memorial – a elementary, grayness Black Forest granite cross resembling a gravestone, and paid for by the villagers – was unveiled by Eaton on Whit Sunday 1937, in the presence of the locals. Information technology sits on the hillside on the very spot where Jack, Ellercamp and Lyons died. The sculpture is effectually 500 metres away from the chief monument, and just a fraction of its size, but in its simplicity and the way it is positioned on the slope towards the village, it captures the drama of that day, and the boys' agonising concluding journey.

Eaton had wanted the inscription to conclude with the line: "Their teacher failed them in the 60 minutes of trial." Only the High german authorities forbade the last judgement. A bare space shows where information technology would have been inserted. In the entrance to the village church, the parents too erected their own memorial, the only one in which the villagers are thanked for coming to the schoolboys' aid.

T he correspondence that passed between the Foreign Office in London and authorities and prosecutors in Germany in the days immediately after the accident reflects how neither side had whatever interest, in the context of such a delicate political climate, in damaging amicable relations. This meant that misgivings expressed past Eaton and by Freiburg'south public prosecutor were ignored.

Keast, described as being in mental and physical shock, had been questioned on 20 Apr by Dr Weiss, Freiburg's country prosecutor, in an interview that Weiss himself afterward admitted had been inadequate. Although Keast admitted the weather had been poor when the party set out, and told of how he had stopped to inquire people the fashion, he made no mention whatsoever of the several warnings they had given him.

On 27 April, 10 days after the disaster, Robert Smallbones, the British consulate general in Frankfurt, wrote to the Foreign Office to say that sure misgivings about Keast's conduct on the tour deserved to be raised. The disaster, he said, would "probably have been avoided" had Keast been in affect in accelerate with the Hitler Youth who, he had been bodacious, would have been happy to accompany the grouping and could accept helped lead them safely out of the blizzard. He recommended that whatever future British school trips to the Black Forest should reach out to the movement. Smallbones also condemned the inadequate way the boys had been dressed.

Yet Smallbones's misgivings got short shrift from the Foreign Part. A letter from Sir Geoffrey Allchin, the head of its consular department, to his superiors, outlined the farthermost German sensitivities over the case. A French radio station had already erroneously accused the German language government of being "to blame for the disaster" and the German regime, he said, was keen to ensure no official or denizen was held in whatsoever way culpable. In a conclusion that effectively put the lid on whatsoever further investigation, Allchin added that Anthony Eden, the foreign minister – who had already written to the citizens of Hofsgrund and Freiburg to express the "gratitude of the people of London" – was of the opinion that "in these circumstances … no cracking importance, if whatever, should be attached to the present allegations against Mr Keast".

And with that, for the Foreign Role at to the lowest degree, apart from a brief exchange over the costs and details of a memorial, the case was effectively closed.

Not that an inquiry was energetically sought past anyone autonomously from Jack Eaton. It would take put both the Strand school and the London County council (LCC) in the bad-mannered position of having to defend themselves over how inadequately planned the trip was, including why approval had been given to one teacher taking accuse of 27 boys. Publicly at least, Keast's schoolhouse and the LCC appeared to support him. At a special two-day meeting held by the education committee at Canton Hall in May 1936, Eaton had railed at Keast and the Strand school's headmaster, Leonard Dawe, too every bit the older boys, who he accused of failing to assistance the younger ones: "Damn you lot! ... and a thousand times damn the pair of you lot cowards and those yous are sheltering."

Only the committee concluded that "any charges of … whatever impropriety" confronting Keast were withdrawn. It offered simply the vaguest recommendations that the arrangements for future tours "should be most advisedly and exhaustively reviewed" in the hope of "rendering incommunicable, then far every bit lies in human power, whatsoever recurrence of such a tragedy".

But Keast'south life would continue to be haunted for years to come up past Jack Eaton. Nor did the education regime let him off the claw quite and then lightly as had at showtime appeared.

In messages written to Mary Beaumont Medd, Keast relayed details of his subsequent dispute with the LCC'south education officeholder, EM Rich, which would suggest that behind airtight doors, Keast's actions were viewed far more than critically than anyone ever admitted either to the parents or to the public. Keast wrote of how Rich had "summoned" him and "quite bluntly" told him that he should not attempt to get ahead with a school skiing trip to Austria that he was planning 8 months on from the Black Forest incident. The decision followed threats made to the schoolhouse by Eaton, who had confronted Keast at the school gates and told him he would not allow the Austria trip to get alee. Keast was forced to write to all the parents whose children were due to accompany him, to tell them the trip was off.

The defeat left him feeling "utterly finished and aimless … It makes me wonder how I shall stand up to the side by side war, if it does come up," Keast confided in Medd. "I feel that I, and the school, and the LCC are completely governed by the homo [Eaton], just as the national government … seemed under the thraldom of Mussolini'south gangsterdom a year agone."

In addition to stalking Keast at the school, Eaton had begun hounding him at his parents' house, where he lived, and Keast was shut to making a criminal complaint. "If I should exist accosted by Eaton this weekend … I shall near certainly assail him, and I believe if I murdered him it really would be the best cease to this miserable concern," he wrote.

Eaton's rage was even felt by those unrelated to the Blackness Forest incident. Peter Tyreman, a former pupil of the Strand schoolhouse, now resident in Canada, vividly recalled about 80 years afterwards, how Eaton approached him on a street about the school "and asked me how I dared to article of clothing the uniform of the schoolhouse which killed his son".

Eaton also wrote a postcard in blood-red ink to his local MP, stating "equally one army war veteran to another I implore you to see that Justice is Washed. Keast is a criminal and should exist tried as such." Exterior his ain business organization, Eaton erected a plaque stating: "I charge Keast with my son's decease."

On what would have been his son'due south 16th birthday, 16 June 1937, Eaton, wearing a black armband, appeared at the s western law court where he was leap over for abusive words and behaviour, including leaving wreaths on Keast'due south doorstep, and standing outside it shouting: "My son has been murdered!"

The court heard how the Eatons had moved from their Clapham Park house after their son's expiry because information technology was too total of memories. They also wanted to be closer to Streatham Park cemetery where their boy was buried, a marble carving of his head and shoulders standing on a 5ft 4in tall headstone – the same height as Jack – marking his grave. Their new home in Crown Lane Gardens was turned into a shrine to their son, total of his schoolboy trophies and pictures of him in his cricket gear and boxing kit.

O n the morning of the 80th anniversary of the Black Wood tragedy, on 17 April 2016, in the Gasthaus zum Hof, where the boys had spent the nighttime after their rescue, a group of villagers sat effectually discussing the minutiae of the events of 1936. They pored over a map and retraced with their fingertips the route the English boys had taken. Over coffee they discussed everything from what time they had reached specific landmarks, to how thick the snow had been and where the snowball fight took identify.

For years, said Michael Lorenz, an industrial chemist, and grandson of one of the brothers involved in the rescue operation, villagers had mulled over what happened. "To this 24-hour interval nosotros're however amazed that those children were sent out so lightly clad. Nobody hither sends their kids outside without anything on their heads in April," he said. Mariele Loy, the village poet laureate, who has retraced the boys' road herself many times, was flummoxed as to how Keast could have relied on such an inadequate map.

For Bernd Hainmüller, it was both his sense of responsibility as a teacher and his curiosity as a historian that gave him the urge to delve deeper for the truth. "Equally a teacher I would not have been able to live with myself if that had happened to me," he said, on a walk to the Engländerdenkmal, or Monument to the English, the bombastic stone structure that still overlooks Hofsgrund. Hail stones were bouncing off the granite and mountain streams bubbled close by. "I'd surely take thrown information technology in afterwards that."

Hainmüller has spent more than a decade researching the disaster, popularly referred to locally as the Engländer Unglück (Englishmen'southward misadventure). A warm and cheerful 68-twelvemonth-quondam, he was researching a volume on the Hitler Youth motility in Freiburg when he stumbled across the monument, prompting him to enquire questions about its origins. "I was struck past the fact at that place is only one version of this story that has been kept alive over the decades," he said. "And that is the legend of unavoidable death in a freak blizzard."

He was very moved by the Hofsgrunders' actions, and the fact they were largely missing from the history of the rescue. Simply the current refugee crunch has brought present-mean solar day concerns to his door. For the by 10 months, Hainmüller and his married woman Hilltrud, also a retired instructor, have devoted their time to teaching German to classes full of Iraqi Kurds, Syrian Yazidis, Afghans and Eritreans. "In a way we were inspired by the Hofsgrunder who went out to help bring back those boys after hearing their cries for aid," he said. "We have to help these people without expecting anything in return. That's essential if life is to mean anything."

On the afternoon of the ceremony, hundreds of villagers, joined by survivors' relatives, packed together nether the sweetness-smelling pine rafters of Hofsgrund'southward newly congenital village hall, to listen to Hainmüller share his findings in an illustrated lecture. Many of them were hearing the precise details for the beginning time.

Chris Clothier from Manchester, the 66-year-erstwhile daughter of Ken Osborne, thanked the villagers, without whom, she said, her father would not have survived. "My father told us piddling of his experience on the mountain," she told them, her vocalisation breaking. "But he often told us of the kindness of the Hofsgrunder and the help they gave without idea for their own safety. We thank you from the bottom of our hearts."

Later, talking to the locals over Black Wood gateau, Clothier's sister Angela Warner spoke of the small details that had simply very slowly emerged over the years, including the bicycle cape her begetter – at 4ft tall, 1 of the smallest in the group – had borrowed from his ain father for the trekking bout. "It probably saved his life as it stopped him from getting soaked, and helped trap the warm air effectually him," she said. There was also the curious lead model of a cathedral he had stubbornly kept until his death in 2010, which but on this trip had she recognised as Freiburg Minster, which the boys had climbed the mean solar day earlier the fatal hike. His entire life, the kitsch souvenir was a reminder to Osborne of how lucky he was to be live.

Two years after losing Jack, the Eatons had another child, a girl called Jacqueline. Merely Eaton's hopes of seeing a public inquiry into the incident were never fulfilled, and his pledge that he would "die fighting this" may take destroyed his mental health. He died in a psychiatric hospital.

Kenneth Keast eventually switched schools, moving to Bedales in 1939, and later to Frensham Heights, where he served as headmaster. All of his former schools say they have no record of him beyond his name and length of service. He died in 1971.

One of the boys, Stanley C Few, went on to serve in the regular army, although he informed his superiors every bit soon as he joined upwards that he could non be expected to fight the Germans, as they had saved his life. He was sent to fight in Asia instead. Writing to a local 55 years after the Black Woods tragedy, Few said that while it was hard to think the boys' names, their faces, personalities and the sense of friendship they had shared had e'er stayed with him. The memories of their ordeal were every bit fresh as on the twenty-four hours it had happened.

"At times nosotros were walking in a trench of the deeply drifted snow laboriously fabricated by whoever was leading u.s. … hour after hr … with not i of us knowing exactly what lay in the future."

Additional research by Richard Nelsson

-

Main Image: Stadtarchiv Freiburg

Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, or sign upward to the long read weekly electronic mail here.

vanwagonerthosell.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jul/06/fatal-hike-became-nazi-propaganda-coup

0 Response to "After the May 3rd Incident Became Obsessed With Depicting Human Suffering in His Art"

Post a Comment